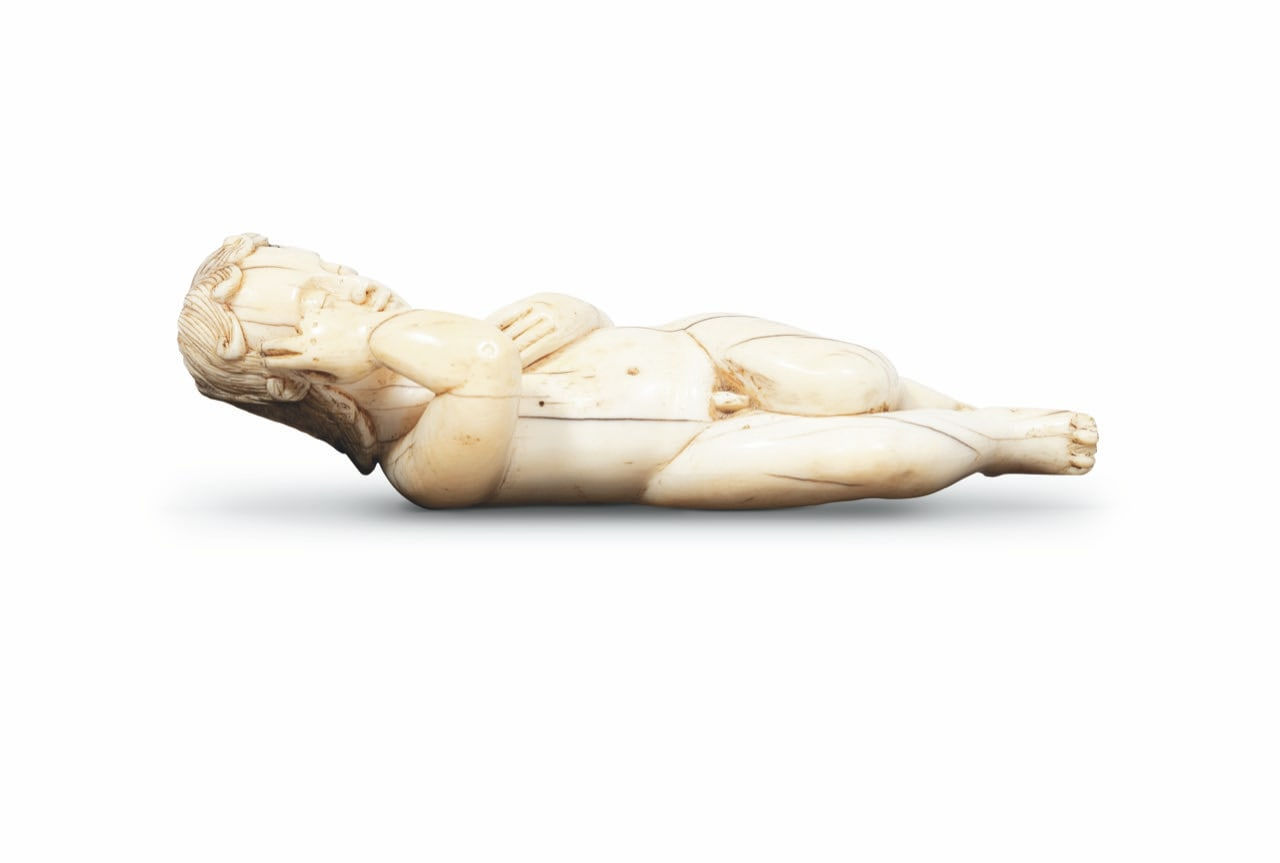

Menino Jesus Deitado, Sul da China, prov. Zhangzhou, c. 1600-1620

Marfim

3.0 x 12.5 x 5.0 cm

F1427

Further images

Provenance

Carmen Vargas, Espanha

Menino Jesus Dormindo produzido no sul da China, durante as primeiras décadas do século XVII. Magistralmente entalhado em marfim de elefante, o Menino está representado nu, numa postura reclinada em decúbito lateral direito, com o rosto e o torso em supinação (voltados para cima). Os membros inferiores são assimétricos, formando uma “posição em quatro” ou “torção semi-reclinada”, com a perna direita praticamente estendida e a esquerda fletida. A colocação dos membros superiores é igualmente distintiva: a mão esquerda repousa sobre o peito, enquanto o braço direito está dobrado, com a mão quase a tocar a têmpora.

Esta pose subtil tanto transmite serenidade, como um delicado dinamismo. O alinhamento relaxado dos membros inferiores sugere um estado de vulnerabilidade; a mão esquerda evoca introspecção e a direita, na têmpora, um gesto pensativo ou protector. A assimetria do corpo - perna dobrada sobre a outra e braço a tocar a têmpora - sugere uma subtil alusão à futura Paixão. Por outro lado, a rotação sugere um estado intermédio - nem em completo em repouso, nem totalmente alerta - paralelo ao papel do Menino como intermediário entre o Céu e a Terra.

No contexto da missão jesuítica na China, na passagem do século XVI para o século XVII, a postura reclinada e vulnerável simbolizaria a humanidade de Cristo, prefigurando a Sua Paixão, em consonância com os esforços jesuítas para enfatizar a Salvação através do sofrimento. A refinada representação de Jesus, combinando serenidade e dinamismo, expressa a sua natureza dual como divino e humano, alinhando-se com os ideais neo-confucionistas chineses de harmonia (hé) entre os reinos espiritual e material.

Talhada em luxuoso marfim com elevado nível de sofisticação artística, esta pequena estatueta terá por certo cativado as sensibilidades estéticas chinesas, facilitando a acomodação cultural e reforçando a sua eficácia na devoção privada e na instrução teológica. Através das suas qualidades tácteis e simbólicas, esta figura promoveria a oração meditativa, deste modo transmitindo visualmente os princípios fundamentais do Cristianismo.

A iconografia do Menino Jesus dormindo parece ter sido concebida por Giacomo Francia (c. 1447-1517) nos inícios do século XVI, numa gravura onde é representado como tendo adormecido sobre a cruz. Numa tabuleta acima do Menino, lê-se a inscrição latina “Ego dormio et cor meum vigilat”, um versículo do Cântico dos Cânticos (5:2): “Eu durmo, mas o meu coração vela”; e abaixo, junto à coroa de espinhos (um dos Arma Christi), numa filactera lê-se “In somno meo requies”, ou “No meu sono, encontro descanso”. No entanto, essa atitude é bastante diferente da posição do marfim chinês, sendo representada na gravura em decúbito lateral esquerdo, ligeiramente virado para baixo, com os membros inferiores e superiores dobrados, utilizando os braços como almofada. Aludindo à alma contemplativa que permanece vigilante mesmo quando o corpo dorme, a gravura pode ser interpretada em termos marianos, como uma alusão ao papel protector assumido por Maria, consciente do destino do seu filho desde o momento do seu nascimento.Esta associação mariana pode também ser observada em gravuras europeias dos finais do século XVI, que se sabe terem circulado na Ásia e servido de modelo para representações locais. Entre elas encontra-se O Sono de Jesus, de Hieronymus Wierix, provavelmente publicado pouco antes de virado o século XVII. Esta iconografia aparece também numa pintura de 1591 de Francesco Vanni (ca. 1563/1564-1610), destinada ao cataletto da Compagnia di Santa Caterina em Siena, que Vanni reproduziu depois numa gravura de 1598, acompanhada da inscrição latina “Ego dormio e[t] cor meum vigilat’. As muito influentes e amplamente difundidas gravuras dos irmãos Wierix devem ter fornecido a inspiração para o gesto de tocar a têmpora direita, tal como vemos na nossa estatueta chinesa. Baseando-se numa gravura anterior de Diana Scultori (1547-1612), Hieronymus publicou uma gravura intitulada Origo casti cordis (“Origem do coração casto”), que apresenta também o mesmo texto bíblico.

Na Península Ibérica, este tema e iconografia conheceram maior desenvolvimento pelo renomado pintor barroco Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682), activo em Sevilha. Murillo criou uma série de imagens que retratam a infância de Jesus que, com o tempo, se enraizaram de forma profunda na arte espanhola, tanto na pintura como na escultura. As suas variações sobre o tema - incluindo uma pintura de ca. 1660 no Museu do Prado, Madrid (inv. P001003), que representa o Menino Jesus numa postura semelhante, com as pernas dobradas e a mão esquerda sobre o peito - incorporam com frequência atributos do seu martírio, prefigurando a sua Paixão e morte. Estas obras funcionavam então como metáforas visuais, concebidas para levar o espectador a reflectir sobre temas teológicos profundos.

É possível que esta figura do Menino Jesus adormecido repousasse originalmente numa almofada entalhada em marfim ou, em alternativa, sobre uma base de madeira esculpida, semelhante às encontradas em raras figuras coevas do Menino Jesus Bom Pastor Adormecido. Outro Menino Jesus Adormecido, representado como o Bom Pastor (19,4 cm de comprimento), com uma túnica de lã aberta e a almofada original com suas quatro borlas, é conhecido e foi publicado enquanto rara peça chinesa de Seiscentos. Em tudo comparável quanto à qualidade do entalhe e idênticos pormenores estilísticos, como as covinhas dos nós dos dedos, é uma estatueta (16,4 cm de comprimento) da colecção do já desaparecido arquitecto português Fernando Távora (1923-2005) no Porto. Tal como a nossa, esta figura também não apresenta almofada.

A origem chinesa desta rara escultura em marfim é evidente no estilo distintivo que apresenta, em particular nos caracóis do cabelo, que se assemelham aos que encontramos em marfins chineses corretamente identificados. Entre eles encontra-se uma importante estatueta em marfim (19,5 cm de altura) no Museu Hermitage, em São Petersburgo (inv. ЛН-939), que representa Avalokiteśvara, o bodhisattva da Compaixão, conhecido localmente como Guānyīn, literalmente “Aquele(a) que percebe os sons (clamores) do mundo”. Reflectindo desenvolvimento posterior da iconografia de Guanyin, esta figura do Hermitage apresenta-se sentada e segurando uma criança do sexo masculino, um tipo conhecido como Guanyin Portadora de Filhos (Sòngzǐ Guānyīn).

Na viragem para o século XVII, durante a crescente presença de missionários católicos no sul da China, mulheres chinesas estéreis rezavam à Virgem Maria por filhos, sendo provável que esta iconografia local possa ter sido concebida enquanto representação ambígua da Virgem com o Menino. Os missionários jesuítas referiam-se a Guanyin como a “Deusa da Misericórdia”, sublinhando os paralelos entre a sua iconografia e a de Nossa senhora. De forma notória, o penteado da Guanyin do Hermitage, com seu entalhe linear, bem como o tratamento do nariz, das pálpebras e da boca, aproxima-se bastante dos estilemas escultóricos que observamos no nosso Menino Jesus Dormindo.

This Sleeping Christ Child was made in South China during the first decades of the seventeenth century. Masterfully carved from elephant ivory, the Child is depicted completely naked, reclining in a partially twisted supine posture. He lies horizontally, with his face and torso facing upwards (supine position) but slightly rotated to the right (lateral recumbent). His lower limbs are asymmetrical, forming a ‘figure-four position’ or ‘semi-recumbent twist’, with the right leg nearly extended and the left slightly bent over it. The placement of his upper limbs is equally distinctive: the left-hand rests on his chest, while the right arm is bent, with the hand almost touching His temple. This nuanced pose conveys both serenity and subtle dynamism. The relaxed alignment of the lower limbs suggests an unguarded state, the left hand evokes introspection, and the hand at His temple hints at a pensive or protective gesture.

The body’s asymmetry, with one leg bent over the other and one arm touching the temple, may subtly allude to the future Passion. Meanwhile, the slightly turned posture suggests an intermediate state—neither fully at rest nor fully alert—paralleling the Christ Child’s role as an intermediary between Heaven and Earth.

During missionary work in China at the turn of the seventeenth century, the reclining, vulnerable posture symbolised Christ’s humanity and prefigured his Passion, aligning with Jesuit efforts to emphasise Salvation through his suffering. The nuanced depiction of the infant Christ, balancing serenity and dynamism, encapsulates his dual nature as both divine and human, resonating with Chinese Neo-Confucian ideals of harmony (hé) between the spiritual and material realms.

Made from luxurious ivory with refined artistry, the figure must have appealed to Chinese aesthetic sensibilities, facilitating cultural accommodation and enhancing its efficacy in private devotion and theological instruction. Through its tactile and symbolic qualities, this ivory carving fostered meditative prayer while visually conveying key tenets of Christianity.

The iconography of the sleeping Christ Child appears to have been devised by Giacomo Francia (ca. 1447-1517) in the early sixteenth century, exemplified by an engraving in which the Child is depicted as having fallen asleep on the cross. In a tablet above the Child, a Latin inscription reads ‘Ego dormio et cor meum vigilat’, a verse from the Song of Songs (5:2), meaning ‘I sleep, but my heart waketh’; while below, beside a crown of thorns (one of the Arma Christi), a scroll bears the words ‘In somno meo requies’, or ‘In my sleep, I find rest’. The Child’s sleeping posture in the engraving, however, differs significantly from that of the Chinese ivory. In the engraving, the Child is depicted in a left recumbent position, slightly rotated downwards, with bent lower and upper limbs, the arms serving as a pillow. Alluding to the contemplative soul that remains watchful even as the body sleeps, the engraving can also be interpreted in Marian terms, as a reference to Mary’s protective role. From the moment of his birth, Mary was aware of her son’s destiny, a theme subtly evoked by the imagery.

This Marian association can also be observed in late sixteenth-century European prints, which are known to have circulated in Asia and served as models for local depictions. Among these is The Sleep of Jesus by Hieronymus Wierix, likely published just before the turn of the seventeenth century. This iconography also appears in a 1591 painting by Francesco Vanni (ca. 1563/1564-1610) for the cataletto of the Compagnia di Santa Caterina in Siena, which Vanni later reproduced as an etching in 1598, accompanied by the Latin inscription ‘Ego dormio e[t] cor meum vigilat’. The highly influential and widely circulated prints by the Wierix brothers must have provided the source for the gesture of touching of the right temple, as seen in the Chinese carving. Based on an earlier engraving by Diana Scultori (1547-1612), Hieronymus published a print title Origo casti cordis (‘Origin of the chaste heart’), which also featured the same biblical text.

In Iberia, this theme and iconography were further developed by the renowned Baroque painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618–1682), active in Seville. Murillo created a series of images depicting the infancy of Jesus, which over time became deeply ingrained in Spanish art, both in painting and sculpture. His variations on the theme—including a c. 1660 painting at the Museo del Prado, Madrid (inv. P001003), showing the Christ Child in a similar posture with bent legs and his left hand resting on his chest—often incorporate attributes of his martyrdom, prefiguring his Passion and death. These works function as visual metaphors, designed to prompt viewers to contemplate profound theological themes.

It is possible that this figurine of the sleeping Christ Child originally rested on an ivory-carved pillow or, alternatively, on a carved wooden base, similar to those found on rare contemporary figurines of the Sleeping Christ Child as the Good Shepherd. Another Sleeping Christ Child, depicted as the Good Shepherd (19.4 cm in length), with an open fleece tunic and its original pillow adorned with four tasselled corners, is known and has been published as a rare Chinese carving from the seventeenth century. Comparable in carving quality and specific stylistic details, such as knuckle dimples, is a figurine (16.4 cm in length) from the collection of the late Portuguese architect Fernando Távora (1923-2005) in Porto. Like the present example, this figurine also lacks a pillow.

The Chinese origin of this rare ivory carving is evident in its distinctive style, particularly the curls of the hair, which closely resemble those found on securely attributed Chinese carvings. Among these is an important ivory figurine (19.5 cm in height) in the Hermitage, St Petersburg (inv. ЛН-939), depicting Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of Compassion, locally known as Guānyīn (‘Perceiver of Sounds’). Reflecting a later development in Guanyin’s iconography, this Hermitage figurine depicts her seated and holding a male child, a type known as Guanyyin as the Bringer of Sons (Sòngzǐ Guānyīn).

At the turn of the seventeenth century, during the growing presence of Catholic missionaries in South China, sterile Chinese women prayed to the Virgin Mary for sons. This local iconography may have been intended as an ambiguous portrayal of the Virgin and Child. Jesuit missionaries referred to Guanyin as the ‘Goddess of Mercy’, highlighting the parallels between her imagery and that of the Virgin Mary. Notably, the Hermitage Guanyin’s hairstyle, with its linear carving, as well as the treatment of the nose, eyelids, and mouth, closely matches the carving style of the Sleeping Christ Child analysed here.

Hugo Miguel Crespo

Esta pose subtil tanto transmite serenidade, como um delicado dinamismo. O alinhamento relaxado dos membros inferiores sugere um estado de vulnerabilidade; a mão esquerda evoca introspecção e a direita, na têmpora, um gesto pensativo ou protector. A assimetria do corpo - perna dobrada sobre a outra e braço a tocar a têmpora - sugere uma subtil alusão à futura Paixão. Por outro lado, a rotação sugere um estado intermédio - nem em completo em repouso, nem totalmente alerta - paralelo ao papel do Menino como intermediário entre o Céu e a Terra.

No contexto da missão jesuítica na China, na passagem do século XVI para o século XVII, a postura reclinada e vulnerável simbolizaria a humanidade de Cristo, prefigurando a Sua Paixão, em consonância com os esforços jesuítas para enfatizar a Salvação através do sofrimento. A refinada representação de Jesus, combinando serenidade e dinamismo, expressa a sua natureza dual como divino e humano, alinhando-se com os ideais neo-confucionistas chineses de harmonia (hé) entre os reinos espiritual e material.

Talhada em luxuoso marfim com elevado nível de sofisticação artística, esta pequena estatueta terá por certo cativado as sensibilidades estéticas chinesas, facilitando a acomodação cultural e reforçando a sua eficácia na devoção privada e na instrução teológica. Através das suas qualidades tácteis e simbólicas, esta figura promoveria a oração meditativa, deste modo transmitindo visualmente os princípios fundamentais do Cristianismo.

A iconografia do Menino Jesus dormindo parece ter sido concebida por Giacomo Francia (c. 1447-1517) nos inícios do século XVI, numa gravura onde é representado como tendo adormecido sobre a cruz. Numa tabuleta acima do Menino, lê-se a inscrição latina “Ego dormio et cor meum vigilat”, um versículo do Cântico dos Cânticos (5:2): “Eu durmo, mas o meu coração vela”; e abaixo, junto à coroa de espinhos (um dos Arma Christi), numa filactera lê-se “In somno meo requies”, ou “No meu sono, encontro descanso”. No entanto, essa atitude é bastante diferente da posição do marfim chinês, sendo representada na gravura em decúbito lateral esquerdo, ligeiramente virado para baixo, com os membros inferiores e superiores dobrados, utilizando os braços como almofada. Aludindo à alma contemplativa que permanece vigilante mesmo quando o corpo dorme, a gravura pode ser interpretada em termos marianos, como uma alusão ao papel protector assumido por Maria, consciente do destino do seu filho desde o momento do seu nascimento.Esta associação mariana pode também ser observada em gravuras europeias dos finais do século XVI, que se sabe terem circulado na Ásia e servido de modelo para representações locais. Entre elas encontra-se O Sono de Jesus, de Hieronymus Wierix, provavelmente publicado pouco antes de virado o século XVII. Esta iconografia aparece também numa pintura de 1591 de Francesco Vanni (ca. 1563/1564-1610), destinada ao cataletto da Compagnia di Santa Caterina em Siena, que Vanni reproduziu depois numa gravura de 1598, acompanhada da inscrição latina “Ego dormio e[t] cor meum vigilat’. As muito influentes e amplamente difundidas gravuras dos irmãos Wierix devem ter fornecido a inspiração para o gesto de tocar a têmpora direita, tal como vemos na nossa estatueta chinesa. Baseando-se numa gravura anterior de Diana Scultori (1547-1612), Hieronymus publicou uma gravura intitulada Origo casti cordis (“Origem do coração casto”), que apresenta também o mesmo texto bíblico.

Na Península Ibérica, este tema e iconografia conheceram maior desenvolvimento pelo renomado pintor barroco Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682), activo em Sevilha. Murillo criou uma série de imagens que retratam a infância de Jesus que, com o tempo, se enraizaram de forma profunda na arte espanhola, tanto na pintura como na escultura. As suas variações sobre o tema - incluindo uma pintura de ca. 1660 no Museu do Prado, Madrid (inv. P001003), que representa o Menino Jesus numa postura semelhante, com as pernas dobradas e a mão esquerda sobre o peito - incorporam com frequência atributos do seu martírio, prefigurando a sua Paixão e morte. Estas obras funcionavam então como metáforas visuais, concebidas para levar o espectador a reflectir sobre temas teológicos profundos.

É possível que esta figura do Menino Jesus adormecido repousasse originalmente numa almofada entalhada em marfim ou, em alternativa, sobre uma base de madeira esculpida, semelhante às encontradas em raras figuras coevas do Menino Jesus Bom Pastor Adormecido. Outro Menino Jesus Adormecido, representado como o Bom Pastor (19,4 cm de comprimento), com uma túnica de lã aberta e a almofada original com suas quatro borlas, é conhecido e foi publicado enquanto rara peça chinesa de Seiscentos. Em tudo comparável quanto à qualidade do entalhe e idênticos pormenores estilísticos, como as covinhas dos nós dos dedos, é uma estatueta (16,4 cm de comprimento) da colecção do já desaparecido arquitecto português Fernando Távora (1923-2005) no Porto. Tal como a nossa, esta figura também não apresenta almofada.

A origem chinesa desta rara escultura em marfim é evidente no estilo distintivo que apresenta, em particular nos caracóis do cabelo, que se assemelham aos que encontramos em marfins chineses corretamente identificados. Entre eles encontra-se uma importante estatueta em marfim (19,5 cm de altura) no Museu Hermitage, em São Petersburgo (inv. ЛН-939), que representa Avalokiteśvara, o bodhisattva da Compaixão, conhecido localmente como Guānyīn, literalmente “Aquele(a) que percebe os sons (clamores) do mundo”. Reflectindo desenvolvimento posterior da iconografia de Guanyin, esta figura do Hermitage apresenta-se sentada e segurando uma criança do sexo masculino, um tipo conhecido como Guanyin Portadora de Filhos (Sòngzǐ Guānyīn).

Na viragem para o século XVII, durante a crescente presença de missionários católicos no sul da China, mulheres chinesas estéreis rezavam à Virgem Maria por filhos, sendo provável que esta iconografia local possa ter sido concebida enquanto representação ambígua da Virgem com o Menino. Os missionários jesuítas referiam-se a Guanyin como a “Deusa da Misericórdia”, sublinhando os paralelos entre a sua iconografia e a de Nossa senhora. De forma notória, o penteado da Guanyin do Hermitage, com seu entalhe linear, bem como o tratamento do nariz, das pálpebras e da boca, aproxima-se bastante dos estilemas escultóricos que observamos no nosso Menino Jesus Dormindo.

This Sleeping Christ Child was made in South China during the first decades of the seventeenth century. Masterfully carved from elephant ivory, the Child is depicted completely naked, reclining in a partially twisted supine posture. He lies horizontally, with his face and torso facing upwards (supine position) but slightly rotated to the right (lateral recumbent). His lower limbs are asymmetrical, forming a ‘figure-four position’ or ‘semi-recumbent twist’, with the right leg nearly extended and the left slightly bent over it. The placement of his upper limbs is equally distinctive: the left-hand rests on his chest, while the right arm is bent, with the hand almost touching His temple. This nuanced pose conveys both serenity and subtle dynamism. The relaxed alignment of the lower limbs suggests an unguarded state, the left hand evokes introspection, and the hand at His temple hints at a pensive or protective gesture.

The body’s asymmetry, with one leg bent over the other and one arm touching the temple, may subtly allude to the future Passion. Meanwhile, the slightly turned posture suggests an intermediate state—neither fully at rest nor fully alert—paralleling the Christ Child’s role as an intermediary between Heaven and Earth.

During missionary work in China at the turn of the seventeenth century, the reclining, vulnerable posture symbolised Christ’s humanity and prefigured his Passion, aligning with Jesuit efforts to emphasise Salvation through his suffering. The nuanced depiction of the infant Christ, balancing serenity and dynamism, encapsulates his dual nature as both divine and human, resonating with Chinese Neo-Confucian ideals of harmony (hé) between the spiritual and material realms.

Made from luxurious ivory with refined artistry, the figure must have appealed to Chinese aesthetic sensibilities, facilitating cultural accommodation and enhancing its efficacy in private devotion and theological instruction. Through its tactile and symbolic qualities, this ivory carving fostered meditative prayer while visually conveying key tenets of Christianity.

The iconography of the sleeping Christ Child appears to have been devised by Giacomo Francia (ca. 1447-1517) in the early sixteenth century, exemplified by an engraving in which the Child is depicted as having fallen asleep on the cross. In a tablet above the Child, a Latin inscription reads ‘Ego dormio et cor meum vigilat’, a verse from the Song of Songs (5:2), meaning ‘I sleep, but my heart waketh’; while below, beside a crown of thorns (one of the Arma Christi), a scroll bears the words ‘In somno meo requies’, or ‘In my sleep, I find rest’. The Child’s sleeping posture in the engraving, however, differs significantly from that of the Chinese ivory. In the engraving, the Child is depicted in a left recumbent position, slightly rotated downwards, with bent lower and upper limbs, the arms serving as a pillow. Alluding to the contemplative soul that remains watchful even as the body sleeps, the engraving can also be interpreted in Marian terms, as a reference to Mary’s protective role. From the moment of his birth, Mary was aware of her son’s destiny, a theme subtly evoked by the imagery.

This Marian association can also be observed in late sixteenth-century European prints, which are known to have circulated in Asia and served as models for local depictions. Among these is The Sleep of Jesus by Hieronymus Wierix, likely published just before the turn of the seventeenth century. This iconography also appears in a 1591 painting by Francesco Vanni (ca. 1563/1564-1610) for the cataletto of the Compagnia di Santa Caterina in Siena, which Vanni later reproduced as an etching in 1598, accompanied by the Latin inscription ‘Ego dormio e[t] cor meum vigilat’. The highly influential and widely circulated prints by the Wierix brothers must have provided the source for the gesture of touching of the right temple, as seen in the Chinese carving. Based on an earlier engraving by Diana Scultori (1547-1612), Hieronymus published a print title Origo casti cordis (‘Origin of the chaste heart’), which also featured the same biblical text.

In Iberia, this theme and iconography were further developed by the renowned Baroque painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618–1682), active in Seville. Murillo created a series of images depicting the infancy of Jesus, which over time became deeply ingrained in Spanish art, both in painting and sculpture. His variations on the theme—including a c. 1660 painting at the Museo del Prado, Madrid (inv. P001003), showing the Christ Child in a similar posture with bent legs and his left hand resting on his chest—often incorporate attributes of his martyrdom, prefiguring his Passion and death. These works function as visual metaphors, designed to prompt viewers to contemplate profound theological themes.

It is possible that this figurine of the sleeping Christ Child originally rested on an ivory-carved pillow or, alternatively, on a carved wooden base, similar to those found on rare contemporary figurines of the Sleeping Christ Child as the Good Shepherd. Another Sleeping Christ Child, depicted as the Good Shepherd (19.4 cm in length), with an open fleece tunic and its original pillow adorned with four tasselled corners, is known and has been published as a rare Chinese carving from the seventeenth century. Comparable in carving quality and specific stylistic details, such as knuckle dimples, is a figurine (16.4 cm in length) from the collection of the late Portuguese architect Fernando Távora (1923-2005) in Porto. Like the present example, this figurine also lacks a pillow.

The Chinese origin of this rare ivory carving is evident in its distinctive style, particularly the curls of the hair, which closely resemble those found on securely attributed Chinese carvings. Among these is an important ivory figurine (19.5 cm in height) in the Hermitage, St Petersburg (inv. ЛН-939), depicting Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of Compassion, locally known as Guānyīn (‘Perceiver of Sounds’). Reflecting a later development in Guanyin’s iconography, this Hermitage figurine depicts her seated and holding a male child, a type known as Guanyyin as the Bringer of Sons (Sòngzǐ Guānyīn).

At the turn of the seventeenth century, during the growing presence of Catholic missionaries in South China, sterile Chinese women prayed to the Virgin Mary for sons. This local iconography may have been intended as an ambiguous portrayal of the Virgin and Child. Jesuit missionaries referred to Guanyin as the ‘Goddess of Mercy’, highlighting the parallels between her imagery and that of the Virgin Mary. Notably, the Hermitage Guanyin’s hairstyle, with its linear carving, as well as the treatment of the nose, eyelids, and mouth, closely matches the carving style of the Sleeping Christ Child analysed here.

Hugo Miguel Crespo

1

of

37

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.