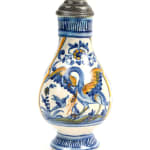

Pichel Aludindo à Eucaristia/ A Pitcher Alluding to the Euraristy, lisboa, 1635-1650

faiança portuguesa / portuguese faience

Alt. / H. : 20 cm

C680

Further images

A rare, first-half of the 17th century container known as a pitcher, used for taking wine from large vessels and barrels. The elegant semi-circular handle links the ovoid shaped body, raised on a conical foot, to the elevated cylindrical neck.

Decorated in antimony-yellow and cobalt-blue pigments on a pewter-white background, the central body section, of elegant lobulated cartouche, depicts a well-known mythological scene of a pelican feeding her young her own blood. The remaining surfaces are filled by foliage and flower motifs and exuberant, apparently aquatic plants, emerging from a rock outcrop by a balustrade. On the neck and foot a vertical band and filleted border lock the composition. The pitcher is mounted with a contemporary German pewter lid of engraved ownership mark.

The pelican is symbolic of the Passion of Christ and of the Holy Communion. As Christ has given His blood to feed His people, so does the pelican, by wounding its own breast to feed its own blood and flesh.

On the basis of its format and decorative composition, the present pitcher is a valuable example of symbiosis between Chinese and European culture. Of the former, the cobalt-blue decoration on the white enamelled ground, allied to the mimicry of foliage elements and their distribution, clearly derived from Ming porcelain models. Of the latter the recognizable western shape, as well as the decorative Italian majolica inspiration, particularly in the depiction of the main central scene and use of antimony-yellow pigment.

Portuguese ceramic pitchers, produced in large numbers for export to Northern German cities - where the pewter lid was applied on arrival – followed typologies of contemporary German jugs. The absence of specific decorative models however, forced Portuguese potters to explore their own decorative solutions, resulting in a hybridism reconciling northern shapes to Portuguese emerging exotic tastes.

Almost exclusively exported to that European region, these jugs have been wrongly referred to as “Hamburg faience” pitchers, being recorded in some northern museums under this classification. These particular daily use wares were in stark contrast with exports to other markets, which favoured alternative typologies such as plates and display pieces.

The artist’s creativity is, in this instance, valued as a taste adjusted to Renaissance Europe. Effectively, other countries, namely those of the European coasts such as Holland, that cherished Chinese porcelain, preferred pieces that adopted distant exoticism and cobalt-blue monochromes in the Ming taste.

Bibliography:

Lissabon – Hamburg, Kunst und Gewerbe Museum, Hamburg

Decorated in antimony-yellow and cobalt-blue pigments on a pewter-white background, the central body section, of elegant lobulated cartouche, depicts a well-known mythological scene of a pelican feeding her young her own blood. The remaining surfaces are filled by foliage and flower motifs and exuberant, apparently aquatic plants, emerging from a rock outcrop by a balustrade. On the neck and foot a vertical band and filleted border lock the composition. The pitcher is mounted with a contemporary German pewter lid of engraved ownership mark.

The pelican is symbolic of the Passion of Christ and of the Holy Communion. As Christ has given His blood to feed His people, so does the pelican, by wounding its own breast to feed its own blood and flesh.

On the basis of its format and decorative composition, the present pitcher is a valuable example of symbiosis between Chinese and European culture. Of the former, the cobalt-blue decoration on the white enamelled ground, allied to the mimicry of foliage elements and their distribution, clearly derived from Ming porcelain models. Of the latter the recognizable western shape, as well as the decorative Italian majolica inspiration, particularly in the depiction of the main central scene and use of antimony-yellow pigment.

Portuguese ceramic pitchers, produced in large numbers for export to Northern German cities - where the pewter lid was applied on arrival – followed typologies of contemporary German jugs. The absence of specific decorative models however, forced Portuguese potters to explore their own decorative solutions, resulting in a hybridism reconciling northern shapes to Portuguese emerging exotic tastes.

Almost exclusively exported to that European region, these jugs have been wrongly referred to as “Hamburg faience” pitchers, being recorded in some northern museums under this classification. These particular daily use wares were in stark contrast with exports to other markets, which favoured alternative typologies such as plates and display pieces.

The artist’s creativity is, in this instance, valued as a taste adjusted to Renaissance Europe. Effectively, other countries, namely those of the European coasts such as Holland, that cherished Chinese porcelain, preferred pieces that adopted distant exoticism and cobalt-blue monochromes in the Ming taste.

Bibliography:

Lissabon – Hamburg, Kunst und Gewerbe Museum, Hamburg

Publicações

ROQUE, Mário, From Lisbon to Japan, Lisboa: São Roque, 2019 (pp. 350-351)Receba as novidades!

* campos obrigatórios

Processaremos os seus dados pessoais que forneceu de acordo com nossa política de privacidade (disponível mediante solicitação). Pode cancelar a sua assinatura ou alterar as suas preferências a qualquer momento clicando no link nos nossos emails.